January 4, 2017 - 2:30pm

By Dane Gibson

After spending almost 40 years as a research scientist at Environment Canada, Dr. Max Bothwell is finally hanging up his hip waders. But not before he helped solved a seemingly unsolvable mystery that stumped scientists from around the world – including Bothwell himself – and had him slogging through algae-clogged rivers in countries all over the globe.

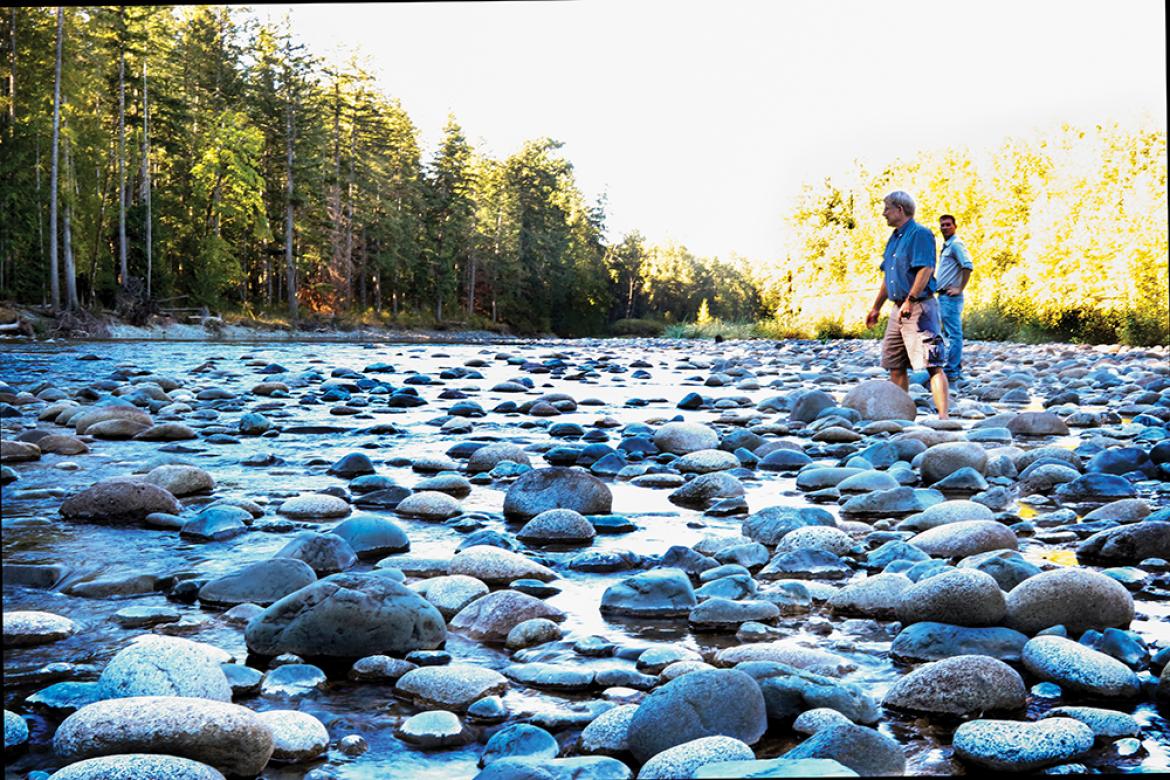

Dr. Bothwell is a Vancouver Island University (VIU) adjunct professor and world-renowned expert in algae and algae growth in rivers. Hired by Environment Canada as a research scientist in 1979, over the next decade he published many scientific papers on the topic. It wasn't until 1993 that he came face-to-face with the mystery that would define his professional life. Seemingly out of nowhere mucus-like, thick gelatinous mats of yellowish -brown algae were found clinging to rocks on the river bottoms of some of Vancouver Island's most pristine rivers. Sometimes stretching for kilometers, it wasn't long before the algae known as Didymo, short for Didymosphenia geminata, got the moniker it would be more commonly identified by - "rock snot."

"I was working in Saskatchewan in 1993 when a friend of mine called from Nanaimo and told me huge algae blooms were happening in some very remote rivers on Vancouver Island. He asked if I could come out to take a look because they had never seen anything like it," said Bothwell.

The first recorded bloom occurred in the Heber River near the Vancouver Island community of Gold River. With the support of Environment Canada and the BC Government's Ministry of Environment, Bothwell arrived and found himself conducting extensive field/laboratory testing in several Vancouver Island rivers as well as exploring historical data records to try and figure out what was causing the phenomenon.

"I studied it for a couple of years and realized I couldn't figure it out. Here I was a world authority on river algal blooms and my final report basically concluded something is happening and I don't know what it is," said Bothwell. "I left the field of periphyton ecology and many years passed without rock snot crossing my mind. It was a problem I couldn't solve so I had to forget about it."

Bothwell says the algae blooms are a concern to governments because the blooms have an impact on the environment including river habitats, water flows and fish spawning grounds. The blooms are also despised by anglers who spend a lot of money to fish unspoiled, remote river systems. In 2004 Bothwell received a call from a colleague in New Zealand. They were dealing with an infestation of Didymo and needed help.

"My friend from New Zealand is on the phone saying, 'Rock snot is taking over several rivers on the South Island of New Zealand, it's a disaster - you have to help us!'" said Bothwell. "As he's talking I'm thinking to myself, 'Oh boy, here we go again.'"

Bothwell spent two years working with a team of biologists in New Zealand to develop a strategy for the New Zealand government to deal with Didymo. Their report concluded, among other things, that Didymo, previously unknown in New Zealand, was likely introduced to the country on felt-soled waders used by anglers who came from all over the world to fish. Because of their work the New Zealand government banned the use of felt-soled waders in the country.

But even after finishing his work in New Zealand, reports of rock snot blooms taking over rivers around the world continued to increase. Bothwell spoke about the issue in places as diverse as Chile and New Hampshire, yet he knew ground zero was Vancouver Island and it got him thinking that something other than movement by fishermen had to be happening.

"I started questioning if introduction by anglers could be causing all of this and decided it couldn't be. I began thinking of the Heber River as the smoking gun," said Bothwell. "Blooms were occurring all over the world now, but why did this start happening on Vancouver Island over 10 years previously? What was so special about this place?"

He refocused his attention and with the help of VIU Department of Chemistry student researchers, they began looking for anything unusual that might have affected the Heber around the time of the first recorded blooms. They combed through fishing license data and historical records, but it was reports from the BC Ministry of Forests that eventually led to solving the mystery.

Donovan Lynch is currently the Science Operations Manager for the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo but 15 years ago, the VIU chemistry graduate started work with Bothwell on a number of projects, including rock snot. Bothwell offered him a job when he was still a VIU student and it led to him working at Environment Canada for eight years.

"I was keenly interested in the rock snot story because I was an avid fly fisher and did a lot of hiking into remote places. During that time we were finding rock snot in areas you just wouldn't expect," said Lynch. "We had sent out papers saying it appeared to be transferred by hip waders and yet we kept seeing it in rivers that weren't being fished. A lot of the work we did back then led Max onto a different path."

The forestry reports they uncovered showed that in the 1980s the BC government started one of the largest forest fertilization programs in the world. They used helicopters to drop more than 1 million kilograms of urea fertilizer on forests to increase tree production. The data showed some of the first drops occurred in the Heber River watershed.

Bothwell now had a solid event he could focus on. After running experiments and looking at water quality data from that time Bothwell focused in on phosphorus levels in the Heber and was shocked by what he found. Instead of phosphorus levels rising in the rivers due to the fertilizer drops, it actually dropped to next to nothing.

"When they started fertilizing the forests it stimulated not just tree growth but all soil microbial activity. The forest floor is a huge network of microorganisms and it was taking up the phosphorus that would usually run into the river," said Bothwell. "We could finally show that the aggressive growth of rock snot is caused by ultra-low phosphorus conditions, something that was very hard to accept. We all knew that adding more nutrients, especially phosphorus, to a river system always equals more algae and here I came face-to-face with the exact opposite of that. It was unbelievable."

Bothwell's discovery brought a new understanding of how and why rock snot behaves the way it does. It's now suspected that the microscopic algae naturally resides in all rivers and climate change-associated environmental changes trigger the exponential growth that causes the blooms.

Bothwell's hypothesis is that climatic warming of landscapes increases the level of biological activity on land and decreases the amount of phosphorus entering rivers, causing conditions similar to the effect of adding urea fertilizer. Add to that increasing levels of nitrogen from fossil fuel use and you get the perfect conditions for the blooms to occur.

Dr. Bothwell is retiring this year having rewritten the scientific understanding of the causes of Didymo blooms, but he won't be settling in to a life of leisure. He will maintain an office at VIU's Fisheries and Aquaculture Department to support research projects, conduct lectures and provide assistance to VIU's International Centre for Sturgeon Studies.

"To me, it feels like I solved my professional life's greatest mystery. Discovering the connection between low phosphorus and rock snot was an amazing 'aha' moment," said Bothwell. "Now I look forward to working with VIU students who will be going off to find their own great mysteries to solve."

*This article originally appeared in the Fall/Winter 2016 issue of VIU Magazine. Check out more stories from the latest issue of VIU Magazine here.

Tags: VIU Magazine