VIU History Professor Dr. Cheryl Krasnick Warsh publishes biography on pioneering physician’s work

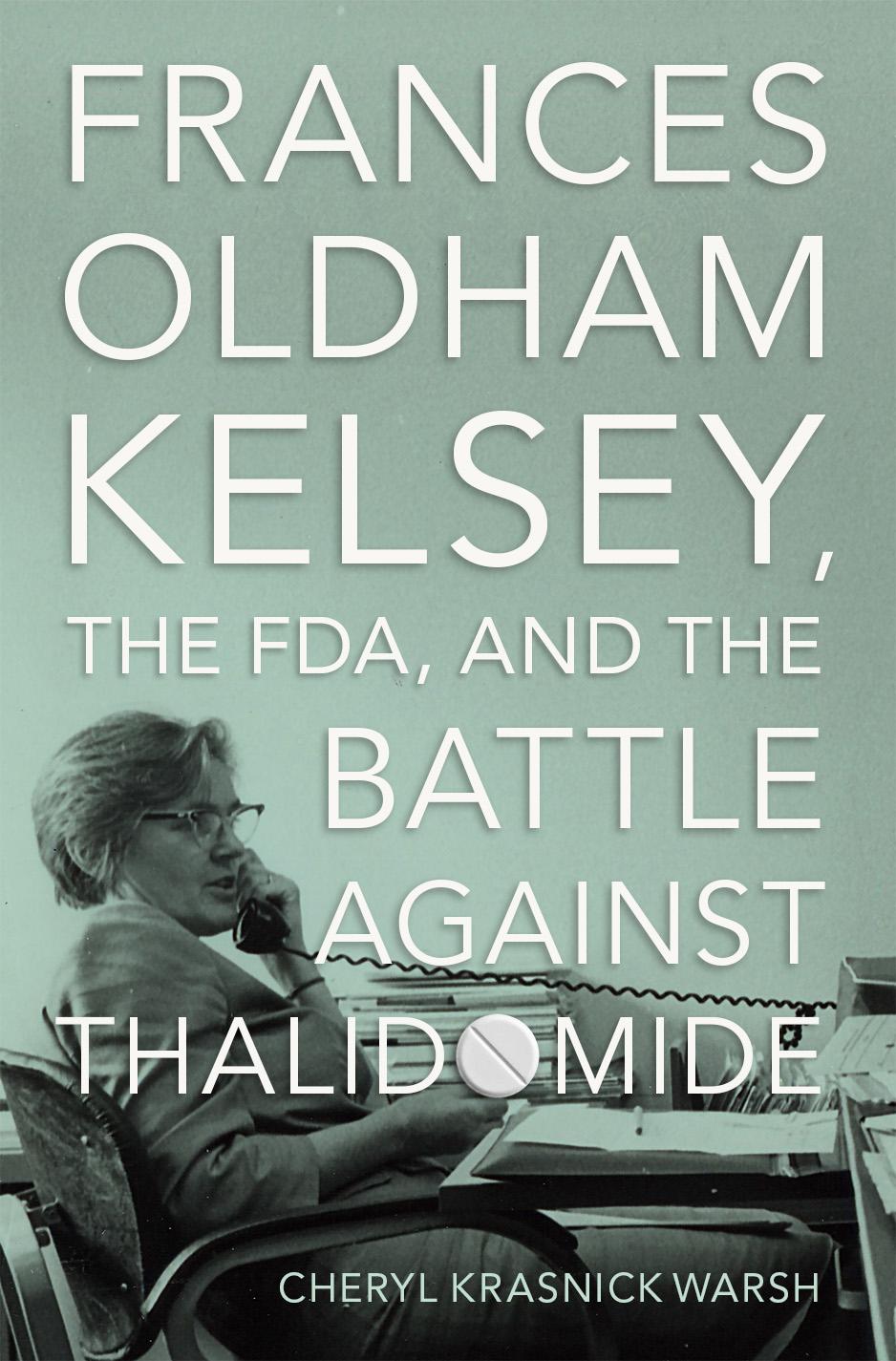

Dr. Cheryl Krasnick Warsh, a Vancouver Island University (VIU) History Professor, recently released her latest book Frances Oldham Kelsey, the FDA, and the Battle against Thalidomide.

The book is a biography of Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey, who saved countless women and children in the United States from the devastating effects of thalidomide, a drug given to women that caused birth defects and deaths. Kelsey was from Cobble Hill, Vancouver Island, and became a pharmacologist and physician. Warsh’s biography sheds light on this pioneering woman’s life and the contributions she made to science.

Warsh used Kelsey’s personal and professional papers as well as interviews to craft the biography. She said there were almost 100,000 uncatalogued documents at the Library of Congress when she started. She worked with students in Washington, DC, to scan and send them to VIU for students here to sort and catalogue.

“There was so much to sift through it was hard to keep cutting for the book, but the students were extremely helpful. They’ve been inspired by the kind of research work they can get here. Through the work-op program, senior undergraduates acquired research experience that is only available to graduate students at larger universities.”

Published in May, the book so far has been reviewed in Harper’s Magazine and The Wall Street Journal. It also has been produced as an audiobook and is featured in two upcoming documentaries.

Warsh is a distinguished medical historian and her studies on psychiatry and addictions influenced the discourse of a generation of scholars. Her thesis on the London Asylum for the Insane and dissertation Moments of Unreason have been cited widely in academia and referenced in media such as the film Beautiful Dreamers and the TV series Murdoch Mysteries. She was inducted as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 2017 for her contributions to the field. She is also known for her editorial leadership as editor-in-chief of the Canadian Bulletin of Medical History and co-editor of the Gender and History journal.

We caught up with Warsh to talk about her new book. Below is a lightly edited transcript of that conversation.

Tell us more about your book Frances Oldham Kelsey, the FDA, and the Battle against Thalidomide and what inspired you to write it.

This book has been a 12-year journey from beginning to end. I had done a previous book called Prescribed Norms, which was about women's health in North America. When I was researching childbirth, I was accessing material on birth defects and found thalidomide, which led me to Frances Kelsey, who was from Cobble Hill, Canada, and I went, “Is that my Cobble Hill here on Vancouver Island?” So immediately I did a little research and found that she lived in Washington, DC, and she was still alive. She was about 94 or 95 at the time. And I just took it from there.

I had no idea how big a project it would be. I just thought it would be interesting to get out of standard social history, which deals more with big themes and social processes and try biography. I thought at the time it would be a narrower focus. Little did I know, because of my subject, how big it would be.

I also was looking for it to be aspirational. I wanted to write a biography where you can experience how people lived their lives. How they overcame challenges. How they ended up being the right person at the right place, at the right time. And how others can model behaviour from what they can get out of it. That's why I found it a very rewarding experience.

How did a woman from Cobble Hill on Vancouver Island become one of the most famous women in the world in 1962?

Frances Kelsey was born in Cobble Hill. She was from a family of British expats. Her father had been in the military and her mother was Scottish gentry. They lived on a gentleman’s farm, and were highly educated, especially Dr. Kelsey’s mother. She wanted her children to be well educated and there were the small private schools in the area that were created for expats by other British immigrants.

Frances Kelsey had an interest in science, and she went down to UVic which was then Victoria College, and it was at Craigdarroch Castle. She was one of a minority of women in Canada that obtained a degree in science and then one of the first to get a master's degree from McGill University. Victoria College was a feeder school of McGill University at the time. She finished her degree there. She was always a pioneer in her field – pharmacology.

She earned a PhD, and conducted research at the University of Chicago, facing many glass ceilings as a woman seeking a permanent position. At the university, she met her husband, also a pharmacologist. They moved to South Dakota for his job. In 1960, she was offered a position at the FDA. By the time she got to the FDA she wasn’t young. She was in her early forties. She had two kids who were in high school and was fairly seasoned by the time she got to the FDA.

What was thalidomide and why was it a watershed for women’s and children’s health?

Thalidomide was a drug that was created in Germany with a very murky provenance. Several board members of the drug company Grüenenthal had served in the Nazi SS. It came out with an awful lot of fanfare. They thought that it was the ideal sedative that you could give to babies, you could give to children, and it would be perfectly safe.

It was very popular in the late 1950s. Then clusters of cases of phocomelia appeared, which is when babies were born with either no arms and legs or had flipper-like appendages for hands coming out of their shoulders. Those were the most obvious defects that came out of thalidomide. But there were heart problems and all kinds of internal disorders. We don't know the full nature of how many babies were affected. It could have been hundreds of thousands. Many would die, many would be stillborn or miscarried.

The US distributor of thalidomide wanted to bring it to market in 1960 for Christmas. This was a hot season for sedatives because people are either depressed or overwhelmed by the work they have to do, and they love a nice pill to relax over the holidays. There was a ton of the drug waiting in warehouses for the FDA to approve. And because it had been approved in Europe when Frances Kelsey started working there, they gave it to her as her third file and they figured it was just a shoo-in.

As a medical reviewer with both a PhD and an MD, she examined medical reports and clinical studies. She said these aren't clinical studies. These are testimonials. There were things doctors said like, “I used this on 15 patients, and it was a wonderful drug. It was terrific.” There were no double-blind studies. There were no proper studies. It was all kind of fishy.

She repeatedly requested more research, angering the company. They harassed her all summer until reports from Europe revealed the drug caused terrible birth defects. Eventually, the company withdrew the application. It was in the United States as an experimental version, but it was never approved and unleashed fully on the market.

It was devastating for women. The most heartbreaking part was that it was prescribed as being a drug that would help problem pregnancies. If you had terrible morning sickness it was supposed to help it. So here you have women who want to save their pregnancies and are taking the drug that's going to ultimately kill their babies. The other problem was it could do the damage in the first eight weeks before a woman knew she was pregnant.

This was a watershed moment. This was the moment when the medical profession recognized that drugs may be harmful to fetuses. Previously women and mothers knew that, as there were all kinds of folktales. But the 20th-century doctors believed these were all old wives’ tales and that you should look at the uterus as being almost like an iron safe and nothing could get through it.

Thalidomide showed how fragile the uterus and fetal environment are, demonstrating that anything a mother ingests can impact it. It taught us to be careful about what we put in our bodies and that doctors don't know everything. The thalidomide tragedy started the women’s health movement.

What was Canada’s experience with thalidomide?

I have a whole chapter on Canada. Canada doesn’t come out very well. Before thalidomide, Canada essentially rubber-stamped drug approvals. The agency only had one or two full-time staff. After the war more new chemicals were coming out. They were not prepared for the chemical revolution that took place.

What was totally reprehensible is that after the reports started coming out, the Canadian drug directorate never followed up on it. Since she was Canadian, one of the first things Dr. Kelsey did was contact the Canadian director and say there were issues with this drug. She said to put an alert on it, but nothing happened. Then she became famous. The Globe and Mail and the Montreal Star started doing reports on thalidomide in Canada. They said, “What about us? What about Canada?”

Canada was considered part of the American drug market, just like the car market, so we were part of their territory. And sure enough, the same salesmen were coming into Canada and selling drugs in Canada. When the reports started coming out, journalists were going to drugstores and saying, “It's still here on the shelf.” A year later, it was still on the shelf.

They would ask pharmacists, “Why do you still have this drug on the shelf?” One pharmacist said it wasn’t for women, only men could use it. The government and Ministry of Health went on the defensive saying “It's not our problem. It's their problem.” They passed the buck back and forth between provincial and federal jurisdiction. The head of the drug directorate said they didn’t need to get rid of it because there weren’t any cases in Canada. They're saying that there's this magical border that the bad effects of the drug won't pass over and Canada is safe. But cases came in Canada soon after. The inaction of Canada after the fact and after its effects were known is what makes it so reprehensible.

What other accomplishments did Kelsey achieve at the FDA after the thalidomide crisis?

She was a big part of creating drug approval protocols in terms of getting consent, and having research trials that are not overly exploitive, or overly painful for no reason. One of her jobs was to go into places like prisons and hospitals where they have a vulnerable population and audit the kind of research studies they're doing and make sure it's all done properly.

There was also a drug called Diethylstilbestrol (DES), which was an estrogen product and was used to fatten up livestock. She was part of getting that drug off the market.

She came to the groundbreaking of the Frances Kelsey Secondary School in Mill Bay. The day before she went to Lake Cowichan. She was in a little boat with her daughters and grandchildren, and somebody went by in a motorboat and cut the wave. She jumped in the air and landed on her back. And they all laughed but then the pain set in because she had broken her back. They took her to the hospital and all they did was give her a Tylenol and send her on her way. She had back problems for the rest of her life. The ground turning was the next day, and she gave her speech. Her voice was a little quiet, but most people didn’t know what happened to her. She did it with a broken back. That to me is a hero.